The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) will soon issue what is likely to be its most significant opinion to date: It will determine whether Europeans continue to have a realistic option to protect their right to privacy online. In November 2023, Meta adopted a “Pay or Okay” approach. Since then, users have been forced to either pay a ‘privacy fee’ of € 251.88 per year or agree to be tracked. The Dutch, Norwegian and Hamburg data protection authorities (DPAs) have therefore requested a binding EDPB opinion on this matter. If ‘Pay or Okay’ is legitimised, companies across all industry sectors could follow Meta’s lead – which could mark the end of genuine consent to the use of European’s data. noyb has now joined forces with 27 other NGOs (including Wikimedia Europe, Bits of Freedom and the Norwegian Consumer Council) to urge the EDPB to issue an opinion that protects the fundamental right to data protection.

- Joint letter to the European Data Protection Board

- DPA’s request for an EDPB opinion on “consent or pay”

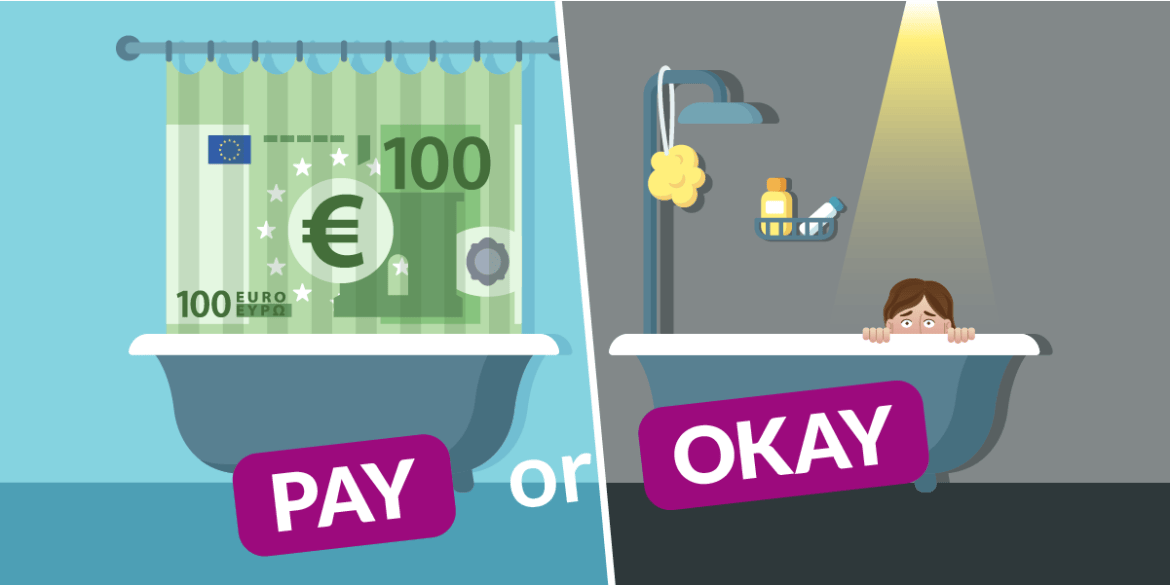

Meta says “pay for your rights”. After the European Court of Justice (CJEU) declared Meta’s handling of user data illegal last July, Meta jumped to the next best option to bypass the GDPR and implemented a so-called “Pay or Okay” system. Since November 2023, Instagram and Facebook users have been forced to either pay a fee of up to € 251.88 a year or agree to be tracked for targeted advertising. In other words: Instead of finally asking for yes/no consent, Meta is charging a € 251.88 fee for clicking the “reject” button. In reality, most people simply have no choice but to accept the exploitation of their data, when confronted with a fee. The effect is clearly illustrated by scientific studies: For example, the CEO of the “Pay or Okay” provider contentpass stated that 99.9 % of visitors agree to tracking when faced with a € 1.99 fee. At the same time, objective surveys suggest that only 3-10 % of users want their personal data to be used for targeted advertising.

Max Schrems: “Under EU law, users have to have a ‘free and genuine choice’ when they consent to being tracked for personalized advertisement. In reality, they’re forced to pay a fee to protect their fundamental right to privacy.”

Pre-ticked boxes are illegal, but a fee to ‘reject’ is okay? The Dutch, Norwegian and Hamburg data protection authorities (DPAs) have now requested an EDPB opinion on this approach, which will determine the future of free consent online. The possible consequences of this opinion go far beyond Meta’s harvesting of user data: If ‘Pay or Okay’ is legitimised, the approach will spread like a wildfire. This can be seen in Germany, where 30% of the top 100 websites already use “Pay or Okay” to drive up consent rates. While the CJEU and the authorities have so far been clear that e.g. “pre-ticked boxes” or reject buttons on the second layer of a banner are illegal, it seems that simply asking for money is not seen as a clear problem. If the DPAs don’t take a clear stance against this, Europeans may quickly lose the ‘genuine or free choice’ to accept or reject the processing of their personal data, which was a cornerstone of the GDPR and has been repeatedly upheld by the CJEU.

Max Schrems: “It is clear that the laissez-faire approach on ‘Pay or Okay’ in some member states is a failure. For example, Germany got flooded with ‘Pay or Okay’ systems in just nine months after the authorities allowed it. The authorities now have the chance to reverse their national approach when this gets voted on in Brussels.”

Failed attempt to support the news media. The first ‘Pay or Okay’ schemes were introduced by struggling news organisations that were losing increasing amounts of advertising revenue. It therefore seems that DPAs have green-lighted such systems in the hope of supporting the news industry. In reality, however, publishers only get the leftover breadcrumbs of ad revenue if people accept tracking. Also, up to 99.9 % of people go for the “Okay” option, leading to minimal sales of paid subscriptions. The real profits form personalized advertisements remain with large corporations like Meta and Google.

Max Schrems: “The hope was that ‘Pay or Okay’ may save news media that lost its advertisement revenue to ‘big tech’. This did not work, as 99.9% refuse to pay to get their own data back. The irony is that ‘big tech’ is now using the loophole for itself.”

Fundamental rights as a luxury good? If a significant number of companies and websites switched to ‘Pay or Okay’, the costs would quickly spiral out of control. The average European has 35 apps installed on their smartphone. If all of these apps followed Meta’s example and charged a fee similar to € 251.88 per year, the price would break most people’s budget. To be more specific, a family of four with just 35 apps per phone would end up with a bill of € 35,263.20 per year. This would make the right to data protection largely unavailable, and not just for the 22.6% of the European population who are currently at risk of poverty or social exclusion.

Max Schrems: “Users deal with hundreds of websites, apps and companies every month. All of them could simply charge a ‘privacy fee’ if you don’t agree that you data is collected, shared or sold. If you do the maths, this adds up to thousands of Euro per year.”

28 NGOs call on EDPB to protect free consent online. The undersigned 28 NGOs and Consumer Rights Organisations (including Wikimedia Europe, Bits of Freedom and the Norwegian Consumer Council) therefore urge the EDPB and all national data protection authorities to strongly oppose ‘Pay or Okay’ in order to prevent the creation of a significant loophole in the GDPR. The EDPB’s opinion will shape the future of data protection and the internet for years to come. It is of utmost importance that the opinion truly guarantees data subjects a ‘genuine and free choice’ over the processing of their personal data.

Max Schrems: “28 civil society organisations now call on the authorities to ensure that fundamental rights do not become a commodity or a luxury good. This is likely the most important decision over EU privacy rights in a decade.”