Today, the EDPB has issued its first decision on "Pay or Okay" in relation to large online platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, as first reported by Politico. This decision prohibits Meta from using an unlawful consent request processing personal data. It seems that by now, Meta has run out of options to continue using people's data for advertising in the EU without a consent mechanism that actually complies with the law.

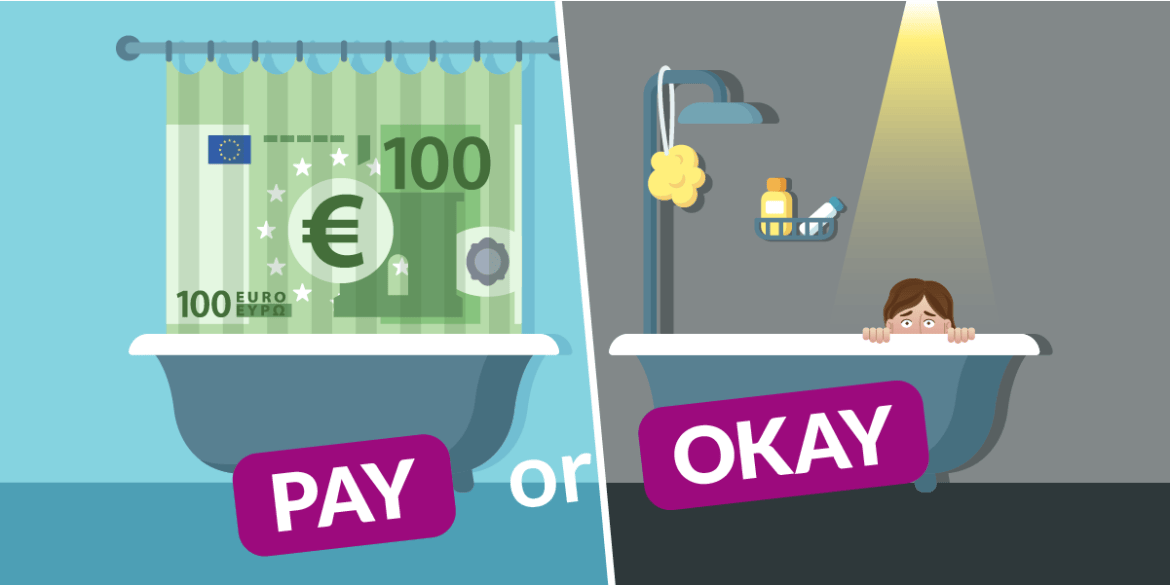

Opinion on large online platforms. As argued in previous cases brought by noyb, the EDPB appears to have followed the only logical understanding of the term "freely given consent" when analysing Meta's "Pay or Okay" system, which charged users more than € 250 per year for Instagram and Facebook if they did not "freely" consent to the use of their personal data. Politico quotes the EDPB as saying "In most cases, it will not be possible for large online platforms to comply with the requirements for valid consent if they confront users only with a binary choice between consenting to processing of personal data for behavioral advertising purposes and paying a fee".

Max Schrems: "Overall, Meta is out of options in the EU. It must now give users a genuine yes/no option for personalised advertising. It can still charge sites for reach, engage in contextual advertising and the like - but tracking people for ads needs a clear 'yes' from users."

Discussion stated - evidence needed. Today's EDPB opinion will need to be analysed in more detail once it is published in full. It is likely to be only a starting point for a wider discussion on "Pay or Okay" in various contexts, given that the EDPB intends to issue further guidelines later this year that go beyond "large online platforms". The core question remains whether a "Pay or Okay" model can meet the legal requirement that consent must be "freely given" and that the "genuine wishes" of the users are upheld. After all, consenting to the processing of personal data is a decision to give up the fundamental right to data protection. Usually, fundamental rights cannot be "sold" or only granted for a fee. The EDPB has so far largely decided in a vacuum, without independent and comprehensive evidence of how a "Pay or Okay" model interferes with users' genuine and free choice.

Max Schrems, Chairman of noyb: "We welcome that the EDPB has started a more nuanced discussion on 'pay or okay' and at least clarified that large platforms cannot use 'pay or okay'. However, we are concerned that today's first opinion is rather cautious and was based on limited facts. Once all the facts are on the table, we are confident that 'Pay or Okay' will be declared unlawful across the board. We know that 'Pay or Okay' shifts consent rates from about 3% to more than 99% - so it is as far from 'freely given' consent as North Korea is from a democracy. It is crucial to get all the relevant numbers for further decisions beyond Meta and larger platforms."

Third option needed. The EDPB also mentioned the possibility of introducing a third option beyond "Pay or Okay", which has so far been largely ignored by the industry. In fact, there are many ways to monetise a website, such as contextual advertising, product placement, paid content or freemium models where certain content is only available for a fee. While the industry tries to limit the discussion to two options ("pay" or "okay"), the EDPB has emphasised that the GDPR does not limit other ways of funding products - even if they may be less profitable.

Pay or Okay is the end of "freely given" consent. As we have warned in recent months, "Pay or Okay" results in massive costs for consumers (easily €35,263.20 for a family of four), that far outweigh publishers' current ad revenues, which often amount to just a few cents. The current average revenue for programmatic advertising in the EU is € 1,41 per user - across all websites per month. In countries like Austria, Germany, France, Spain or Italy visiting the top 100 websites can already cost more than € 1,500 per year if you do not consent to tracking. In last week's background video, we also highlighted the problematic decision-making dynamics of "Pay or Okay", which changes the "free wish" of users from 3% who want to have personalised advertising to up to 99.9% who (unwillingly) click "agree" if the alternative is a hefty bill.

Max Schrems: "When more than 90% of users agree to something they don't want, you don't need a lawyer to see that it's not 'freely given' consent. In fact, 5 years after the GDPR came into force, this is just the latest 'trick' to undermine EU law, or at least delay compliance for a few more years. It is highly problematic that authorities have not already taken a clear position on this. In the cases we have brought in Austria or Germany, we rather see that the authorities turn a blind eye to 'Pay or Okay' because it was first introduced by the news media, which they do not want to interfere with - even though the law is the same for everyone."

Background. Until the GDPR became applicable on 25 May 2018, Meta has used "consent" under Article 6(1)(a) GDPR as the legal basis for processing users' personal data, for example for advertising. Under the GDPR, consent would have to be specific, informed, unambiguous and freely given. Meta feared, that giving users such a yes/no option would limit their options to make money in the EU, so at midnight on 25 May 2018, Meta started arguing that it was part of the user contract to show ads, using Article 6(1)(b) GDPR. This was ruled illegal by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) in 2023. In 2023, Meta then briefly argued that it had a "legitimate interest" to process personal data for advertising under Article 6(1)(f) GDPR, until it began to revert to "consent" under Article 6(1)(a) GDPR - by asking users to consent or pay a fee of up to € 20.99 for Instagram and Facebook combined.

The Norwegian, Dutch and Hamburg data protection authority took "Pay or Okay" back to the EDPB, which has now issued a decision. All these attempts to circumvent the law have been done with the active support of the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC), as the lead regulator of Meta's EU headquarters in Ireland. All of these "agreements" with the Irish regulator were later found to be unlawful by the EDPB or the CJEU.