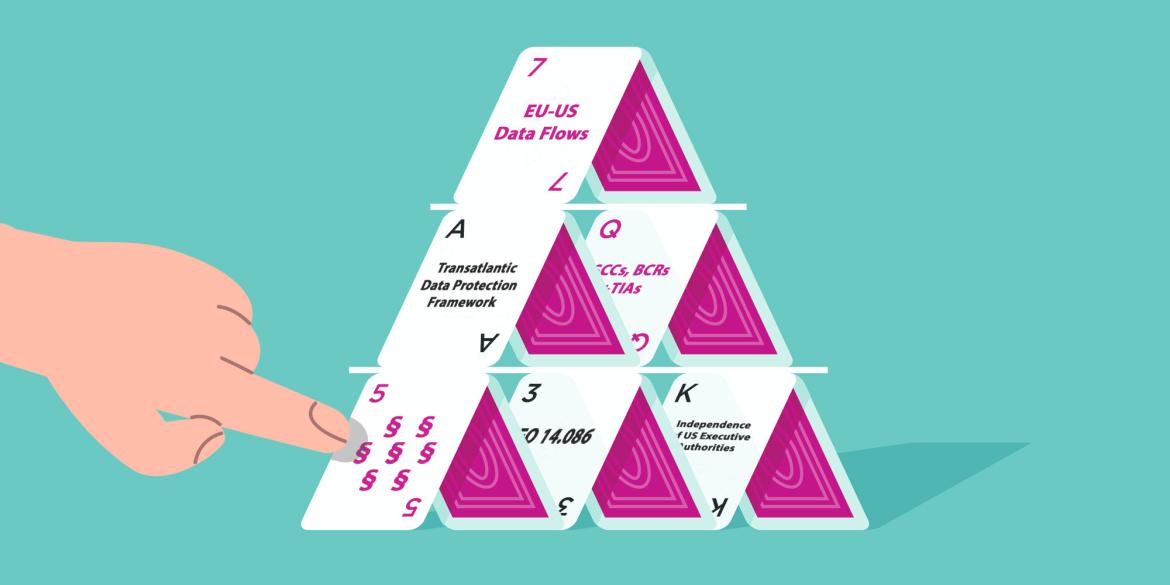

Most EU-US data transfers are based on the “Transatlantic Data Privacy Framework” (TAFPF) or so-called “Standard Contract Clauses” (SCCs). Both instruments rely on fragile US laws, non-binding regulations and case law that is under attack – and is likely blown up in the next months. As instability in the US legal system becomes undeniable and the US shows open signs of hostility towards the EU, it is time to reconsider where our data is flowing – and how long the legal “house of cards” that the EU has built is holding up.

Blog post by Max Schrems

Layers of US and EU law. The “bridge” that the European Commission and previous Democratic US administrations built to allow EU personal data to be processed in the US does not rely on a simple, stable US privacy law. Instead, the EU and the US relied on a wild patchwork of tons of internal guidelines and regulations, Supreme Court case law, US factual “practices” or Executive Orders.

In an attempt to make ends meet, these layers are not supporting each other, but are lined up to generate the thinnest possible connection between EU and US law – meaning that the failure of just one of the many legal elements would likely make most EU-US data transfers instantly illegal. Just like a house of cards, the instability of any individual card will make the house collapse.

Given the enormously destructive approach of the Trump administration, many elements of EU-US transfers are under attack – often times not because of any direct intentions. Instead, the current US administration just widely attacks the US legal system and constitutional fabric (with the help of a highly politicised Supreme Court) – with many potential consequences for EU-US data flows.

1st Likely Point of Failure: FTC independence. This past Monday, the US Supreme Court has heard a case about the independence of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Ever since a case in 1935 (Humphrey's Executor), it is US Supreme Court case law that the US legislator can create “independent” bodies within the executive branch, which is somewhat isolated from the US President.

A previously fringe theory that, under the US Constitution, all powers of the executive must rest with one person only (the President) has now gained traction among US conservative lawyers. This so-called “unitary executive theory” would make any independent authority, such as the FTC, typically unconstitutional. All powers would need to be concentrated in the President.

In Trump v. Slaughter, the US Supreme Court now heard arguments of an FTC commissioner that was removed by Trump despite all independence guarantees in 15 U.S.C. § 41. Based on the comments and questions of the Judges, it is widely believed (see e.g. The Guardian, CNN or SCOTUS Blog) that the conservative majority on the US Supreme Court will side with Trump and (to one extent or another) follow the “unitary executive theory”, overturning FTC independence.

In combination with the US Supreme Court rulings on absolute immunity of the President, the US would thereby move increasingly towards a system where the President is an absolute “King” – at least for four years.

From a European perspective, FTC independence is a crucial element, because Article 8(3) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR) requires that the processing of personal data is monitored and enforce by an “independent” body. In the TADPF (and previously in the “Safe Harbor” and “Privacy Shield” systems), the EU and the US have agreed to give these powers to the FTC in the US – being such an “independent” body. Section 2.3.4. of the TADPF decision of the European Commission highlights the Enforcement role being with the FTC. Recital 61 and Footnote 92 explicitly refer to 15 U.S.C. § 41 as a basis to have the necessary independence guarantees in the US.

No other element in the TADPF has the necessary investigative powers and independence. There is private arbitration as well, but they lack any investigative powers or relevant enforcement powers. Consequently, any TADPF participant must be either governed by the independent FTC or the DoT (for transport organizations).

Trump v. Slaughter is scheduled to be decided in June or July 2026 the latest, but could be decided earlier. So, it’s time to “buckle up” on this one and get prepared.

One path could be to switch to SCCs or BCRs, as they do not require an independent US body for enforcement, but also allow to make the agreement subject to an EU data protection authority. However, there are also massive questions as to how already transferred data can be brought “back” to any EU approved system or even brought “back” to the EU in general. Furthermore, SCCs and BRCs may also be affected by massive shifts in US law (see below).

2nd Likely Point of Failure: Data Protection Review Court. Directly in connection to Trump v. Slaughter, which deals with oversight in the private sector, the parallel question arises on how the so-called “Data Protection Review Court” (DPRC) can still be relied upon as any form of realistic redress against US government surveillance.

The DPRC has many legal issues (you could easily fill a PhD thesis with these problems), but crucially the DPRC is not a real US court – also because it is not established by law. It is actually a group of people within the executive branch that is solely established by an Executive Order of Biden (EO 14.086, see details below). This group of people may at best be called a “tribunal” from the perspective of Article 6 ECHR, but even this claim is probably an overstatement.

The crux is that, in relation to Trump v. Slaughter, the “independence” of this so-called “Court” is not even established by law (as 15 USC § 41 for the FTC), but by EO 14.086, so a merely internal Presidential Order that can be changed at any time.

Logically, if the Supreme Court in Trump v. Slaughter holds that independent executive bodies are unconstitutional, it may well be that any independence claims in EO 14.086 itself are (logically) also unconstitutional. This very much depends on the line of arguments that the Supreme Court will use in Trump v. Slaughter, but we may very likely see this as a direct consequence of any broader ruling.

This problem would expand far beyond the TADPF, because other transfer systems (SCCs or BCRs) rely on so-called “Transfer Impact Assessments” (TIAs) that in turn usually point to EO 14.086 and the DPRC as a ground why any EU controller came to the conclusion that US law may not overrule SCCs or BCRs beyond what is permissible under Article 7, 8 and 47 of the Charter.

If these elements are gone, we are down to Article 49 GDPR for “necessary” transfers (e.g. sending an email to the US, placing an order or booking a hotel or flight), but any “outsourcing” to US cloud providers or SaaS providers would typically not have any viable legal basis anymore.

3rd Likely Point of Failure: EO 14.086. Beyond changes in US constitutional law, there is also Trump himself as a major risk factor. As explained above, basically all forms of EU-US data transfers rely on a Biden Executive Order (EO 14.086). Trump has repeatedly threatened to overturn this EO. Already on the day of his inauguration, media reports indicated he will blindly overturn all Biden EOs. In the end he signed EO 14.148, which only overturned 68 Biden EOs and 11 Biden Presidential Memoranda – but not EO 14.086.

EO 14.148 demands that all “national security” EOs should have been reviewed within 45 days by the National Security Advisor – this should have happened by 06.03.2025. There were no reports about any consequent changes. This does not mean that EO 14.086 was not (partially) overturned in the meantime, as the US President can issue “secret” EOs that change the published EO 14.086. Given the erratic actions by Trump, this is not an unlikely scenario.

In a recent outburst on Biden’s use of the so-called Autopen, Trump has declared all Biden EOs signed with autopens void via a Truth Social posting. It is entirely unclear whether EO 14.086 is such an “autopen” EO and if Trump’s social media postings amount to the formal overturning of these EOs. At the same time, one has to wonder if any NSA official feels overly bound by them anymore. It is also not unlikely that the Truth Social posting may be followed up with a formal EO overturning these Biden EOs.

Another indication that EO 14.086 may be on the line is the “Project 2025” agenda for the conservative takeover of the US government. On page 225, the author lashes out against EO 14.086, the EU and the allegedly unfair treatment of the US - so EO 14.086 is clearly on the agenda. To make things even more absurd, the author (Dustin Carmack) is now the new “Republican” lobbyist of Meta – a company that relies on EO 14.086 to justify its EU-US data transfers that were challenged in Schrems I and Schrems II.

Overall, EO 14.086 could fall any moment – and with it the TADPF and with it almost all TIAS and most SCCs, BCRs.

Many other options. While this goes beyond this blog post, there are many additional questions as to the many other elements used in the TADPF.

There are obviously still the principal questions to the TADPF ever having achieved “essential equivalence”. For example:

- The protections in EO 14.086 were largely a 1:1 copy of an Obama EO called PPD-28, which was rejected by the CJEU in Schrems II.

- The extremely high burdens for redress or the lack of any real right to be heard before the DPRC are miles away from Article 47 of the Charter.

- The commercial data protection principles of the TADPF do not even require a legal basis (as required in Article 8(2) of the Charter and Article 6(1) of the GDPR), but only require to allow for an opt-out.

Furthermore, there were questions about the independence of the PCLOB or the heavy reliance of the EU on (unwritten) “US practices” – when Trump has shown that he and his administration do not even respect laws, let alone previous “practices”.

What can we do? In my view, EU governments and controllers must (more than ever) urgently prepare for very likely hits to EU-US data transfers in the next months. The US National Security Strategy has made it clear that the Trump Administration sees Europe more as an enemy than a partner and that European digital legislation is a core focus point of likely US aggression.

The only long-term solution is (unfortunately) to limit any data transfers to US providers, insofar as they have “possession, custody or control” of European personal data. There may be more offers where all factual access from the US is technically impossible – however, so far the only realistic protection that is available on the market is to switch to European providers.