We are now working on an in-depth analysis, which will be published on noyb.eu in the next days.

First reaction: Executive Order on US Surveillance unlikely to satisfy EU law

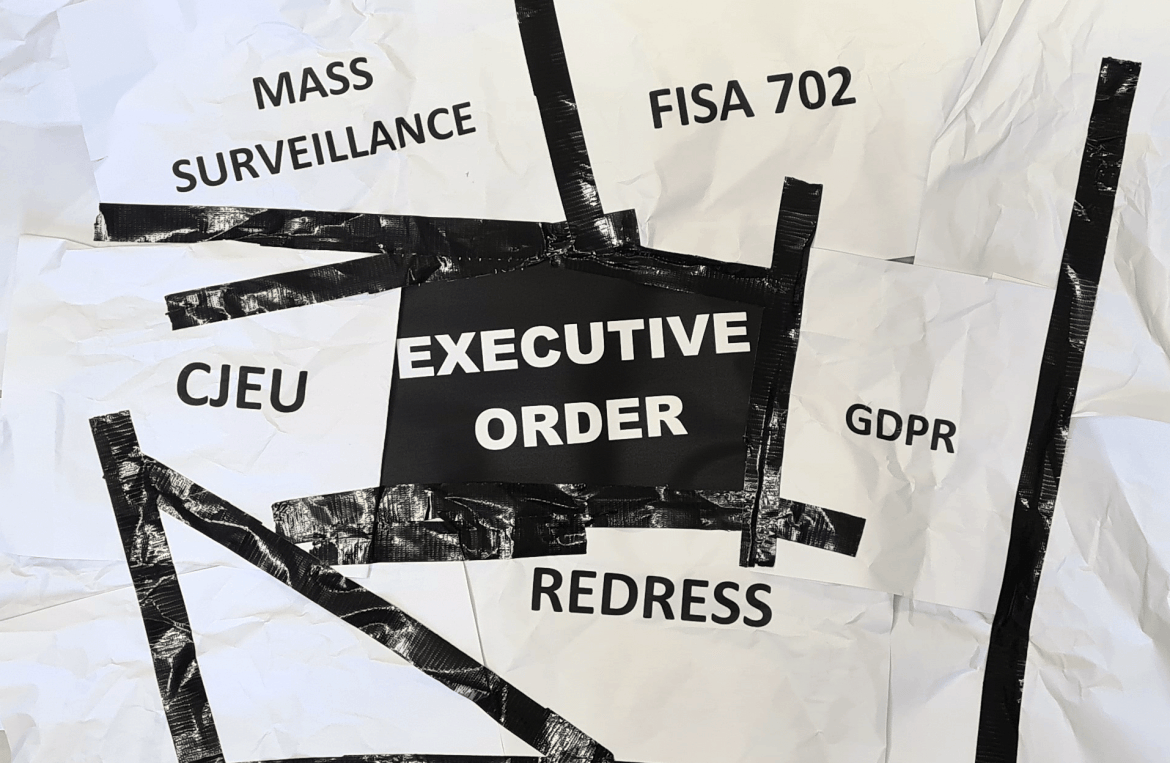

More than six months after an "agreement in principle" between the EU and the US, US President Joe Biden has signed the long-awaited Executive Order that is meant to respect the European Court of Justice's (CJEU) past judgments. This is meant to overcome limitations in EU-US data transfers. The CJEU required (1) that US surveillance is proportionate within the meaning of Article 52 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR) and (2) that there is access to judicial redress, as required under Article 47 CFR. Biden's new Executive Order seems to fail on both requirements. There is continuous "bulk surveillance" and a "court" that is not an actual court.

Executive Order. An Executive Order is an internal directive by the US President within the federal government, but not a law. Previously the matter was regulated by an order by President Obama from 2014, called PPD-28. While it is good to see that our litigation now leads to a reaction by the US President, this internal presidential order will likely not solve the problem:

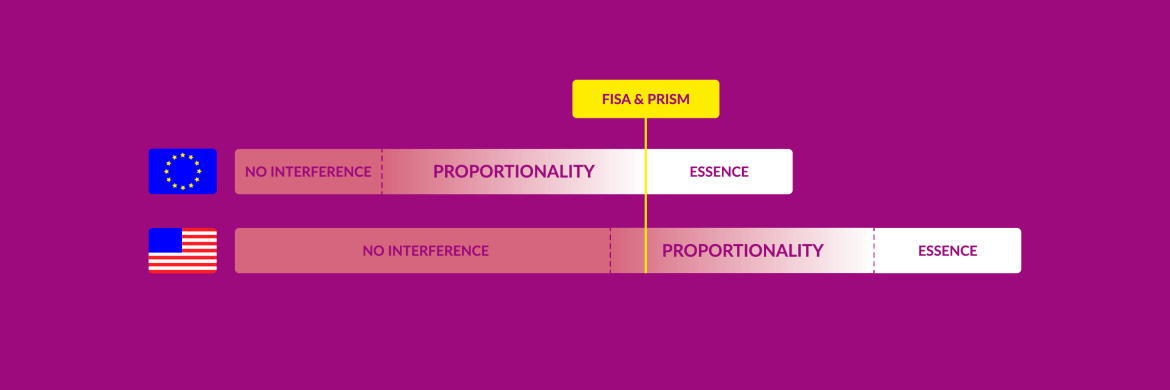

Bulk surveillance continues via two types of "proportionality". The US highlights, that the new executive order uses the wording of EU law ("necessary" and "proportionate" as in Article 52 CFR) instead of the previous term "as tailored as feasible" used in Section 1(d) of PPD-28. This could solve the problem, if the US would follow the same understanding and also apply the proportionality test of the CJEU.

However, despite changing these words, there is no indication that US mass surveillance will change in practice. So-called "bulk surveillance" will continue under the new Executive Order (see Section 2 (c)(ii)) and any data sent to US providers will still end up in programs like PRISM or Upstream, despite of the CJEU declaring US surveillance laws and practices as not "proportionate" (under the European understanding of the word) twice.

How is this possible? It seems, the EU and the US agreed to copy the words "necessary" and "proportionate" into the Executive Order, but did not agree that it will have the same legal meaning. If it would have the same meaning, the US would have to fundamentally limit its mass surveillance systems to comply with the EU understanding of "proportionate" surveillance.

Max Schrems, chair of noyb.eu: "The EU and the US now agree on the use of the word 'proportionate' but seem to disagree on the meaning of it. In the end, the CJEU's definition will prevail - likely killing any EU decision again. The European Commission is turning a blind eye on US law again and allowing the continued surveillance of Europeans."

"Court" is not a real Court. The Executive Order is meant to also add redress. There will now be a two step procedure, with the first step being an officer under the Director of National Intelligence and a second step being a "Data Protection Review Court". However, this will not be a "Court" in the normal legal meaning of Article 47 of the Charter or the US Constitution, but a body within the US government's executive branch. The new system is an upgrades version of the previous "Ombudsperson" system, which was already rejected by the CJEU. It seems clear that this executive body would not amount to "judicial redress" as required under the EU Charter.

Judgment by "Court" already spelled out in Executive Order. Users will have to raise issues with a national body in the EU, who will in turn raise the issue with the US government. The US government will neither confirm nor deny that the user was under surveillance and will only inform the user that there was either no violation or it was remedied (see Section 3(c)(E) of the EO). This also makes the option for an appeal useless, as there is simply nothing to appeal about, as long as the user got this rubber stamp answer. Section 3(i)(d)(H) even goes so far to spell out what the "Court" will respond - no matter you arguments or case: "the review either did not identify any covered violations or the Data Protection Review Court issued a determination requiring appropriate remediation."

Max Schrems, chair of noyb.eu: "We have to study the proposal in detail, but at first glance, it is clear that this 'court' is simply not a court. The Charter has a clear requirement for 'judicial redress' - just renaming some complaints body a 'court' does not make it an actual court. The details of the procedure will also be relevant to see if this can satisfy EU law."

Further research and possible challenge. noyb and its partners will analyse the documents in more detail the coming days and will issue a detailed legal analysis within the next days and weeks. If the Commission decision is not in line with EU law and the relevant CJEU judgments, noyb will likely bring another challenge before the CJEU. In the meantime, US congress will have to re-authorize FISA 702 in 2023, potentially allowing the US legislator to implement meaningful limitations that respect privacy rights of non-US persons.

Max Schrems: "We will analyze this package in detail, which will take a couple of days. At first sight it seems that the core issues were not solved and it will be back to the CJEU sooner or later."

Countries with similar privacy protections can't produce a stable deal? It does not seem logical that two democratic countries that both agree on basic legal principles of privacy, likely produce the third flawed deal in a row:

The Fourth Amendment to the US constitution enshrines a right to privacy and requires that there is probable cause and judicial approval for any wiretap. Equally, the CJEU requires that surveillance must be targeted and there must be judicial approval or review under the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The only difference seems to be that while the EU sees privacy as a human right that applies to any human, the Fourth Amendment only applies to US citizens or permanent residents. In the view of the US, Europeans have no privacy rights. FISA 702 uses that difference in US law and allows surveillance that is illegal under the Fourth Amendment - as long as no Americans are targeted.

Max Schrems: "It is amazing that the EU and the US actually agree that wiretapping needs probable cause and judicial approval. However, the US takes the view that foreigners don't have privacy rights. I doubt that the US has a future as the cloud provider of the world, if non-US persons have no rights under their laws. It is contradictory to me that the European Commission is working on a deal that accepts that Europeans are 'second class' citizens and don't deserve the same privacy rights as US citizens."

US businesses do not need to comply with GDPR. What is striking, is that the European Commission did not request that the so-called "Privacy Shield Principles" are aligned with the GDPR, which is in force since 2018. The principles are largely the same as the previous "Safe Harbor" principles, which were drafted in 2000 and will continue to be used in the new framework. This means that US businesses can continue to process European data without complying with the GDPR. For example, they don't even need a legal basis for processing, such as consent. Under the Privacy Shield US companies only have to offer an opt-out option for users. This is despite the CJEU highlighting that there need to be "essentially equivalent" protections in the US.

Next steps. Now where the US has issued its Executive Order, the European Commission will have to draft a so-called "adequacy decision" under Article 45 of the GDPR. Once the draft decision is issued, the Commission must hear the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), but is not bound by its findings. In addition, the European Member States must be heard and could block the deal. This process can take a couple of months. However, even negative statements by the EDPB and Member States are not binding on the Commission. Once the decision is published, companies can rely on it when sending data to the US and users can challenge it via the national and European courts. This is not expected before spring of 2023, even when it was originally envisioned in fall of 2022.